The funeral home housing Aunt Barbara's ashes

Today my dad and I went to the funeral home and got Aunt Barbara's death certificate (and met two guys with strong Boston accents, but I didn't laugh). Afterwards we walked to my aunt's condo, met the building manager, Leroy, and looked around. It's a beautiful 1920s building with hardwood floors and paneling, and her apartment is full of beautiful antiques. Leroy recognized my dad’s voice from the telephone, but he somewhat belatedly—after we had already entered the apartment and started to look around—asked to see proof of identity, so my dad showed him his driver’s license and the death certificate.

Front entrance to the building in which my Aunt Barbara lived

Front hallway to the building, with the staircase leading to her condo

The condo smelled musty from having been closed up with no open windows.

The front room is a hallway with a few pieces of antique furniture, including a mirror; there’s a fake fountain attached to the wall (it would look rather more appealing if it weren’t for the unplugged electrical cord). To the right is a small room that was originally a servant’s bedroom, and beyond it is a bathroom. Also attached to the front hall is the large living room, full of antiques and with a large bay window overlooking the Charles River. The condo also has a kitchen that is somewhat larger than a kitchenette (particularly longer) and has a white door leading to a back stairway. Otherwise, there’s a small hallway with a closet, Aunt Barbara’s bedroom, a bathroom, and the study. It’s altogether significantly larger than my one-bedroom apartment, and if you wanted you could have a roommate or a guest bedroom in a condo like that.

But let me back up a bit. In the room that was originally a servant’s bedroom, some of the top layer of floorboards had been pulled up. Leroy explained that this was where the body was. Apparently the body was…attached to the floorboards. I stared at the floor, where the boards were missing and the underlying boards were a slightly lighter color than the rest of the floor. I imagined Aunt Barbara lying there. She must have been in this room, standing up, when suddenly her heart gave away and she fell to the floor.

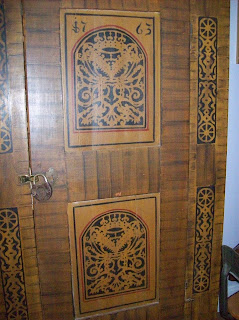

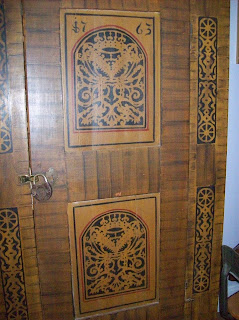

The living room was tidy, if somewhat dusty. The exception to the tidiness was some stacks of boxes, in particular wine boxes. Leroy explained that those had to be removed in order to get to the body. So Aunt Barbara had been using the servant’s room as a storage room. Actually, it did have some furniture: a small table and chair and a large, ornate cabinet with a padlock. Leroy explained that something important might be in that cabinet, but he didn’t know where the key was. So my dad pointed out that an old-fashioned key was another thing to hopefully find.

Leroy showed us the two small desks in the dining room, both possible locations for important papers, and he showed us the library at the back of the condo. It had one wall completely covered with a dark wood bookcase full of books; two tall windows; a computer desk with both a big old computer from perhaps the 1990s and a very small MacBook, in addition to a printer; some other furniture here and there, and a collection of tennis racks decorating the walls. Leroy explained that this was where Aunt Barbara spent a lot of time.

My dad decided to search the living room desks, and I agreed to search the library. Alone in the room, I looked around and opened the windows before I got to work. It was easy to be distracted, especially by all the books on the bookcase and by thoughts of Aunt Barbara living and dying in this condo. I felt mildly disturbed. I turned to the computer desk vicinity and noticed a tall dark file cabinet, so I decided to tackle that first. I found a binder and some papers on top of it, and these at least partially contained printed e-mails, something I hadn’t seen in a long time.

I set aside one of these papers because of the supposed friend who had sent it and whose contact information was on it; this could be someone who would want to participate in the memorial service and could tell us more about Aunt Barbara. That was a concern, in addition to finding a will: my dad wanted to find contact information for friends and colleagues of Aunt Barbara. They could attend the memorial service and would know more about Aunt Barbara so that, if she didn’t have a will, maybe they could help us figure out what to do with Aunt Barbara’s estate.

I opened the top drawer of the tall file cabinet and started to look through it. All the files I glanced at were research, either left over from Aunt Barbara’s PhD work or research that she did more recently. I looked at the desk and then at a wooden box-like piece of furniture on the other side of the desk. I decided to search it for now and closed the file cabinet.

I found a large stack of poetry, mostly limericks, that Aunt Barbara wrote, and I decided I wanted to not only read them but also type them up.

I easily opened this file box by flipping the hinged top out of the way. At the front was a file containing papers related to my grandmother’s death, including her will, and including information on a lawsuit that Barbara went through. She hadn’t gotten along with her mother and had thought she was being cheated, getting less money than my dad; she didn’t take into consideration that my dad had a spouse and three children, while Aunt Barbara herself was single and had no children. However, my dad no doubt pointed this out to her. She still took legal action—but it was against Bank of America, which cheated both her and my dad of thousands of dollars; I don’t remember the details, but it was related to the estate. My dad has hated Bank of America ever since. Another file contained information on stock, and another file contained Aunt Barbara’s two passports, an international driving permit, and three copies of her birth certificate. I took those out and set them aside with the small stack of papers I had picked out to take. As I went through this file box, I came to the conclusion that Aunt Barbara was extremely organized.

And then I found her will. It was in this file box, about halfway back, and in duplicate, with a cover letter from her lawyer, Michael S. Rosen. Thrilled as if I were Indiana Jones discovering a Bastet statue in a cave, I called, “I found the will!” We had only been in the condo for about half an hour. My dad and Leroy came into the room, and we discussed it. I noticed the stamp date of 1991 on the will (I later discovered she wrote the will in 1989), and my dad said there might be a more recent will, so we continued searching the condo.

Leroy was responsible for over ninety condos and had to go do work elsewhere. He said to call if we wanted to look at Aunt Barbara’s car; it was still parked on the September.

I continued searching the library/study. The room had a closet completely filled with bank boxes full of research on economics and such. Two of the bank boxes contained papers from banks and the like, and I began to look through those. On an antique chair across the room from the computer desk was a pair of bright red cloth shopping bags—the kind typically for groceries—advertising one of Aunt Barbara’s banks. Inside was a matching thermos.

In the hallway, I opened the closet door, and what caught my eye was the top shelf: a row of large stuffed toy animals, two of which were penguins. The rest of the closet was less interesting—sheets and such.

Out of curiosity, I wandered into the bedroom. In the center was a large, dark wooden antique bed, and above it hung a painting of Adam and Eve that’s shaped like the underside of a bowl. Facing the foot of the bed is a large old chest of drawers with a few items on top of it, particularly a small wooden multi-drawer jewelry box that resembled a little chest of drawers. My dad had already looked around this room and said, “Barbara had a lot more rings than you, about a hundred.”

One of the dolls I made as a teen and sent Aunt Barbara

I opened a top drawer and sure enough, it was filled with silver and gold finger rings in a variety of designs. The drawer next to it contained a variety of jewelry, and the drawers below that contained even more rings and other miscellaneous jewelry, some of which was certainly vintage. A necklace that particularly caught my eye was small and filigree-like, with small square red stones; it looked potentially a hundred years old. On the chest of drawers was a rectangular whitish stone box, about an inch by an inch and a half in dimension, with a little lid. Inside are finger rings handmade of seed beads. I tried at least two of them on.

Aunt Barbara had even more finger rings than I, and she was a cat person like me. She hasn't had live cats for a few years, but I noticed a big art book on cats, cat bookplates, and a couple of cat brooches (reminiscent of Doctor Who).

When I saw a tall, narrow shelving unit next to the bedroom door, I gasped. On each shelf was a one-of-a-kind cloth doll that I made when I was a teenager and that I mailed to my aunt when I was about twenty years old. It was one of my attempts to reach out to her. I decided that, since I made those dolls, I was entitled to take them. My dad was filling a sort of casual briefcase—one he found in the living room—with significant papers, and it didn’t have enough space for the dolls. I put them in one of the two bright red cloth grocery bags. Next to one of the dolls was an old black and white photo framed with an assemblage of beads and other little things. The photo was of a little boy between a young woman and a young man. I picked up the picture and took it to my dad. “Is this you?” I asked. Yes: this was my dad and my grandparents! I have no memory of ever seeing my grandfather, who died of a heart attack when he was only fifty years old, years before I was born.

On the other side of the bed stood a very large—about three feet tall—carved wooden African statue, probably a deity or (appropriately) an ancestor figure, since I recall that some African statue are tied in with ancestor worship. In the far corner of the room was a cabinet topped by a glass display case containing two carved wooden African statues, approximately eight inches or so tall each.

Even the kitchen contained antiques, in the forms of rectangular carved wooden molds and kitchen and dining items. A large iron object, some sort of tool, hung on the far wall next to a window. The kitchen seemed spare and spotless to me, and I suspect Aunt Barbara may not have been into cooking. The fridge was practically empty; I was glad my dad checked it, because I was afraid of aromatic science experiments. A few ready-made items were in the freezer.

The capacious living room was a treasure trove of antiques. In front of a rather narrow sofa stood a carved wooden coffee table that looked like it came from India and was topped by a protective layer of glass. On top were art books (including one on cats and one on Japanese paintings), some antique knickknacks, and three porcelain Asian fish, in blue, soft green, and orange. In addition to various antique chairs around the room, there was a long table under the bay window and various items decorated the table. My dad later said that the TV was really old, like one we had in the seventies or eighties. I was particularly fascinated by a very large old cabinet and the various objects displayed on it, especially a pair of old cloth black dolls.

Living room

The dining room had a beautiful and predominantly red rug centered on the hardwood floor. Over it was a table with charming seats, two of which were actually benches vaguely resembling two chairs put together. The small top-lifting antique desks were in this room, as was a china cabinet filled mostly with blue and white porcelain. Along one wall was the head and foot of a bed probably from the early twentieth century; it would have been a good addition to the servant’s bedroom.

My dad said that he found medical records—he turned away from them and didn’t want to see the details—and it looks like Aunt Barbara had a lot of health issues. They both inherited money around 2005, and my dad retired and has had a tendency to drive around the United States a lot since then. Over the past few years, he has repeatedly asked Aunt Barbara to accompany him on his travels, and every single time she’d have the excuse of a health problem or another. It happened so many times that he didn’t take her seriously. But it looks like she wasn’t making it up: her health problems were too real.

My dad and I stayed in the condo for about two hours. When we were leaving, he noticed the chain lock was broken and figured out that Leroy must have unlocked the front door when he figured out something was amiss, and when he opened the door, the corpse stench must have been overwhelming. He must have broken the chain to get in. What a horrible way to die—alone and forgotten.